Humanities Research for the Public Good: A CIC Initiative to Connect Colleges and Communities through Student Research and Public Programs (2019–2024)

Introduction

Between 2019 and 2024, the Council of Independent Colleges (CIC) awarded grants to 49 independent colleges and universities through the Humanities Research for the Public Good (HRPG) initiative. The grants supported three cycles of public-facing humanities projects. In each cycle, campus-based teams—including one or more faculty member(s), senior administrators, collections specialists, and student researchers—designed a year-long research project, drawing on the college archives or other special collections, that would then be shared with members of the local community through public activities. Project teams worked in partnership with representatives of one or more off-campus organization(s) who offered subject expertise, hosted events, made connections with local community members, and provided other forms of support. Participating institutions were selected through a competitive application process. For the third funding cycle, institutions that already participated were invited to apply for sustaining grants to fund new projects or to continue activities launched in their initial project year.

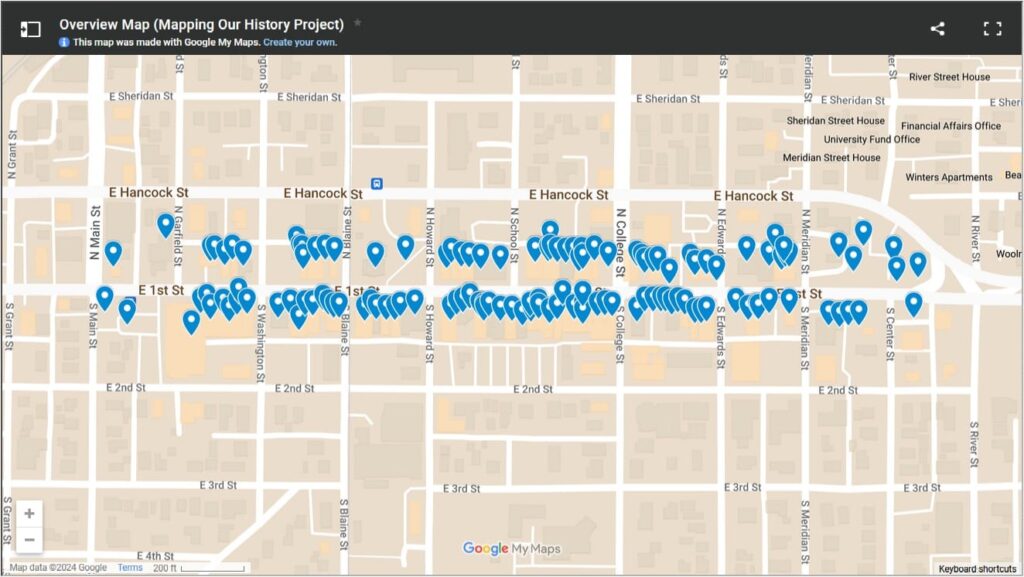

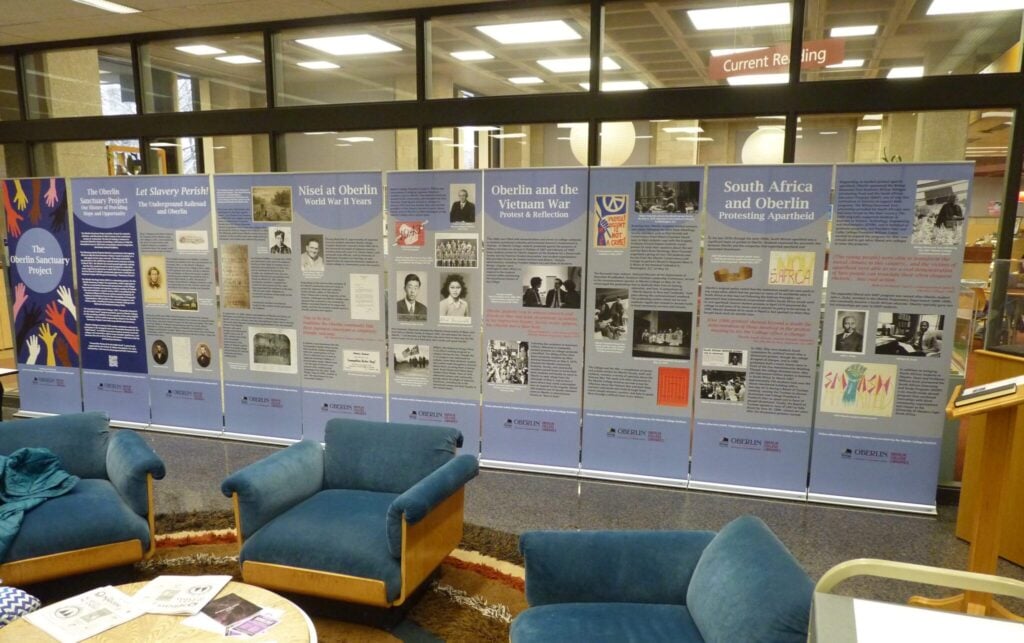

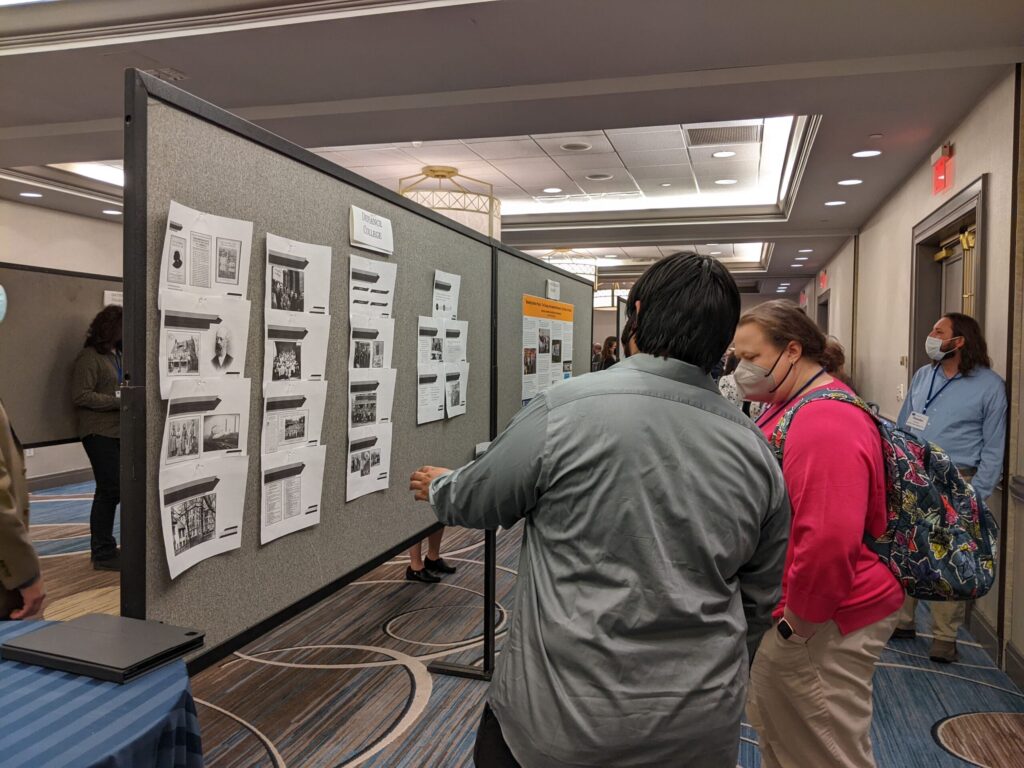

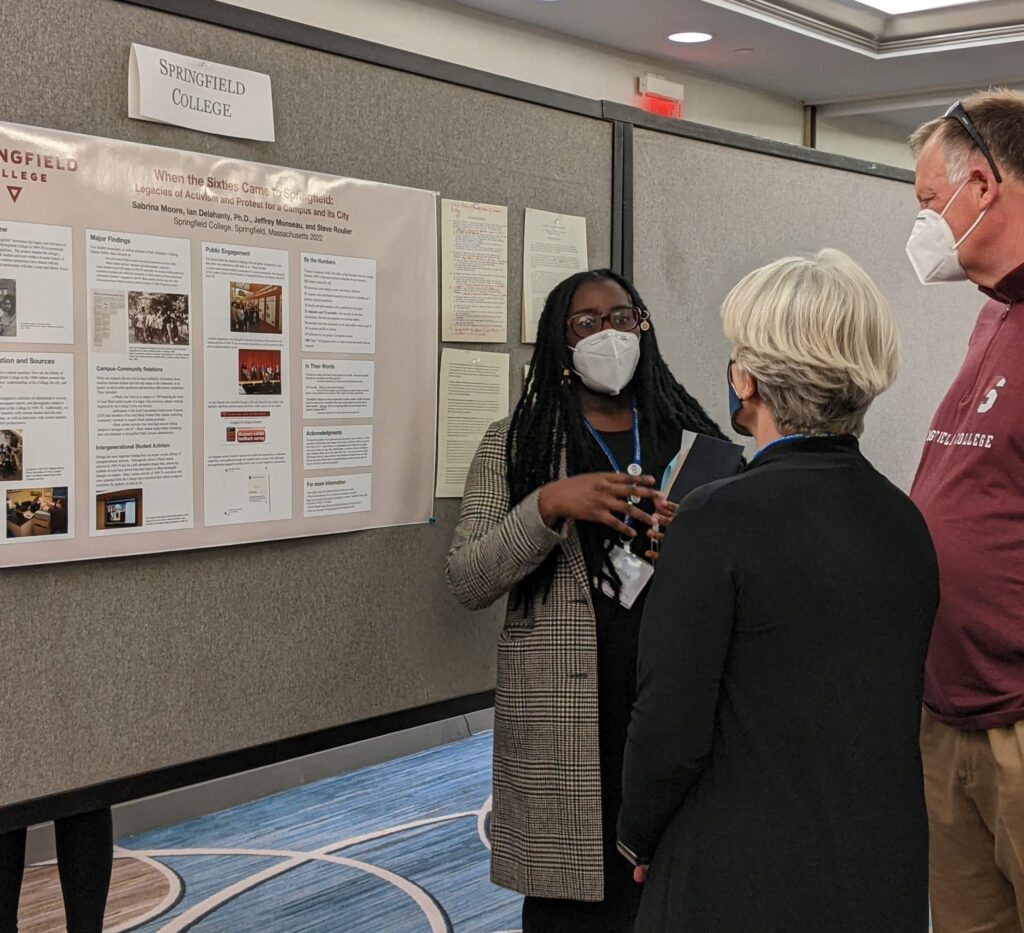

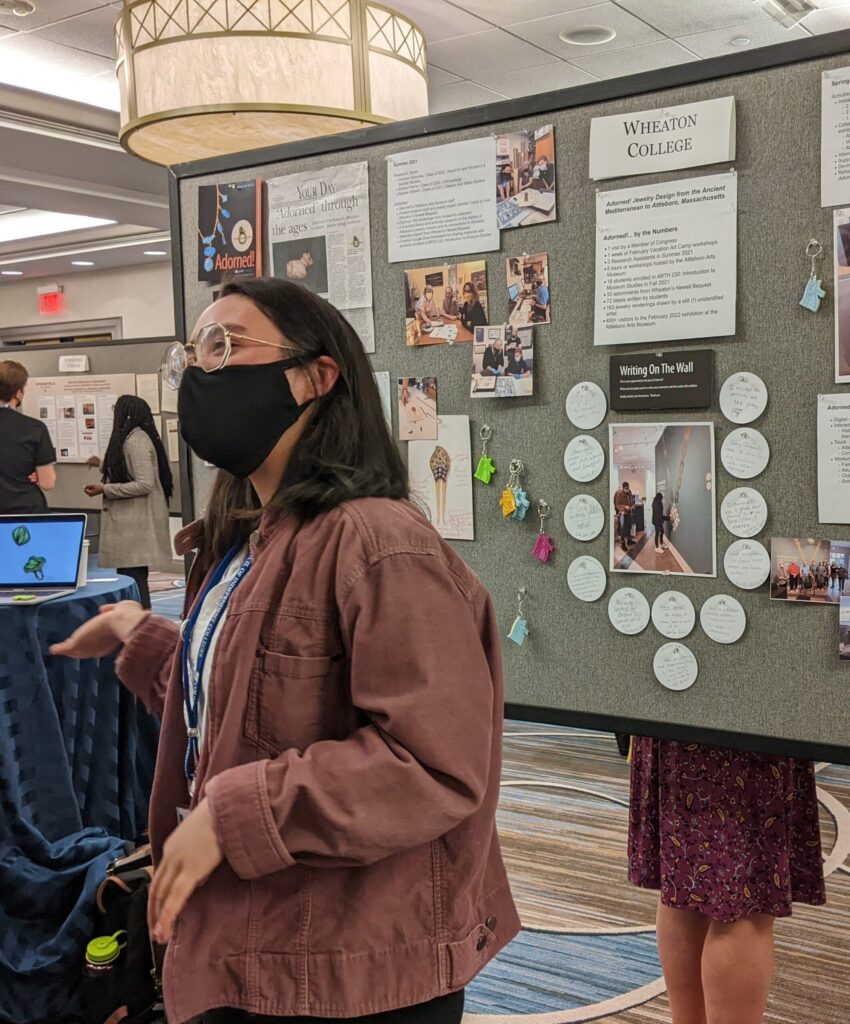

CIC organized workshops at the start and end of each grant cycle, giving the campus teams a chance to deepen their collaborations, develop skills to support public-facing work, and then share their accomplishments with each other. The funded projects explored topics of real community interest—local histories of immigration and migration, urban development, public health, political aspirations and reverses, poetry and other cultural expressions, even the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on local community members. Student researchers presented their work to local audiences both on- and off-campus through exhibitions (digital and in public spaces), podcasts, walking tours, documentary films, community gatherings, and other activities.

The HRPG initiative was designed with the following goals:

- Connect independent colleges and universities with cultural and civic organizations in their local areas for the benefit of both students and the public

- Make better use of existing campus archival collections for teaching, undergraduate research, and public engagement

- Enhance the research, collaboration, and communication skills of students in the humanities disciplines

- Encourage humanities faculty members and collections specialists who work in campus libraries, archives, and museums to apply their expertise to issues of public policy and community concern

- Increase public interest in and appreciation of humanities research

This report offers an overview of the HRPG program and a closer look at some (but not all) of the funded projects. It contains insights and advice that should be helpful to other colleges and universities that also want to support meaningful student work in the public humanities. The report draws on final grant reports submitted by each campus team, formal evaluation surveys, personal observations by the project director and CIC staff director, and a series of group interviews conducted in the summer of 2024. It necessarily privileges the voices of the college and university personnel (faculty, archivists and librarians, administrators) who were responsible for leading the campus teams and reporting on the grants. Whenever possible, comments from students have been incorporated from the project team reports. In retrospect, CIC project staff should have done more to encourage the project teams to capture the voices of community partners and community members who participated in public programs and events. Nonetheless, their reports contained substantial evidence of a positive impact on communities.

Taken together, the HRPG projects demonstrate how applied humanities methods can expand public understanding of the past, present, and future.

Humanities Research for the Public Good was supported by a generous grant from the Mellon Foundation with supplemental funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities.

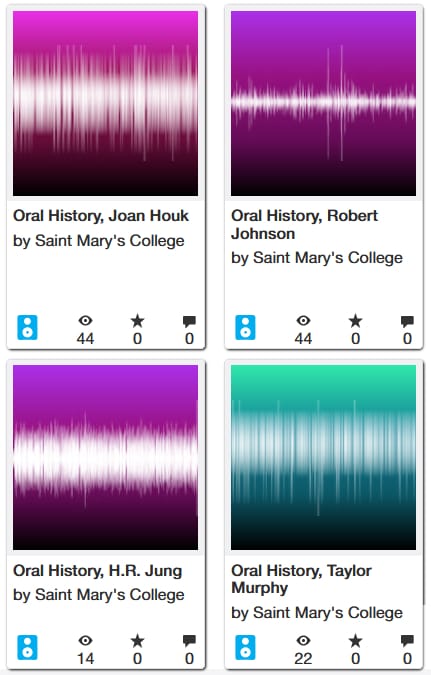

The Funded Projects

Applicants for HRPG grants were not restricted to any particular type of public project, humanities discipline, or list of acceptable topics. However, they were required to draw upon collections held by an institution’s archives, library, or museum; to address a topic of real public interest; to combine student research with public-facing activities; and to engage a community-based organization as a true collaborator. Over the course of a grant year—and often for longer—students, faculty members, and archivists (or other collections experts) worked together to organize and digitize records, conduct primary and secondary research, collect or transcribe oral histories, and then produce exhibitions, podcasts, documentary videos, walking tours, curricular materials, and other virtual and in-person public presentations. Many of their activities were documented in local media coverage and further shared through academic conferences and scholarly publications.

There is a complete list of supported projects, community partners, and links to representative public-facing materials at the end of this page.

Despite the many differences in topic, methods, project structure, and intended outcomes, the grant-supported projects shared several characteristics that contributed to their impact and success. First, the HRPG projects were student-centered: although they involved collaborations among multiple people, their primary intention was to stimulate student learning through the power of project-based and hands-on methods. Second, the HRPG projects created an opportunity for students, faculty members, and administrators to join in a process of shared discovery, a process that sometimes extended to include community members who collaborated with or responded to HRPG programs. Third, HRPG teams used a variety of means to make research and archival materials publicly accessible and meaningful. Through careful planning and by employing rigorous and deliberate methods, HRPG project teams deepened their own knowledge and skills, built new learning communities, and created public research presentations that mattered to communities beyond the campus gates.

Outcomes and Reflections

Students

Public humanities research aligns with many characteristics associated with high-impact educational practices. Regardless of the specific topic of exploration or methods, public humanities projects foster collaboration, encourage discovery and creativity, invite students to expand their understanding of cultures and communities that differ from their own, and promote the consideration of ways that humanities research can help address contemporary issues. They also nurture hands-on learning and require forms of writing that can be applied to the creation of digital and material products for public audiences. When they undertake publicly engaged and project-based research activities, students can develop new skills, explore a variety of career paths, and enhance a sense of connection to faculty members, collections specialists, student peers, community leaders and audiences, and even to familiar places at and around their institutions.

Public humanities projects foster collaboration, encourage discovery and creativity, and invite students to expand their understanding of cultures and communities that differ from their own.

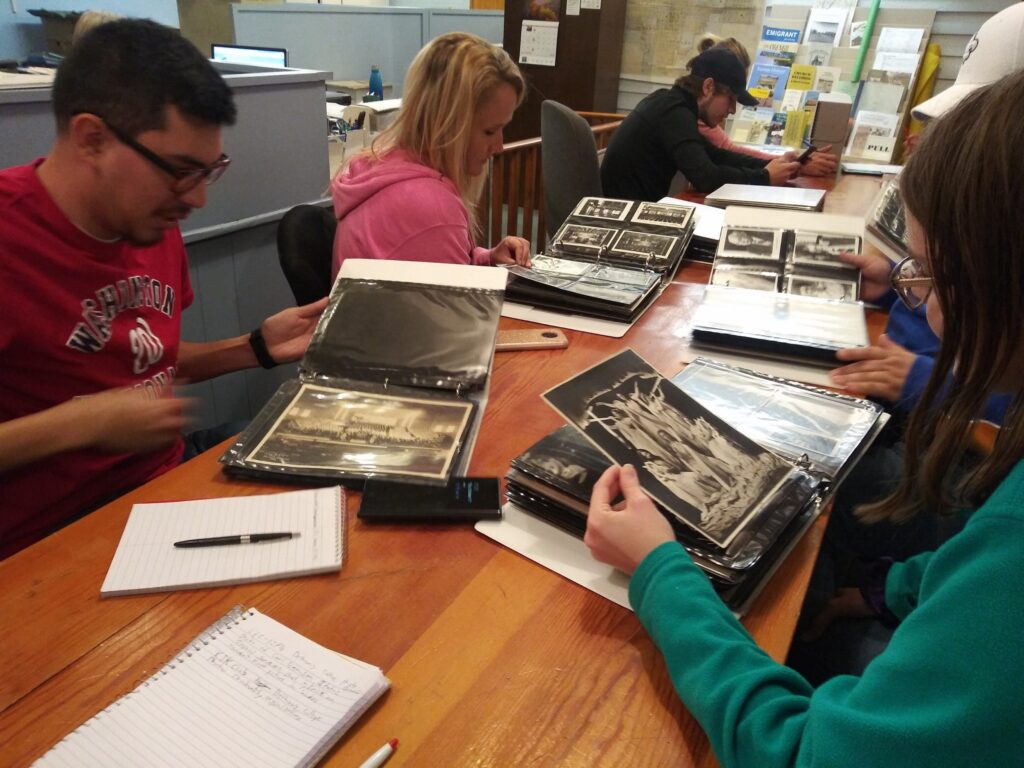

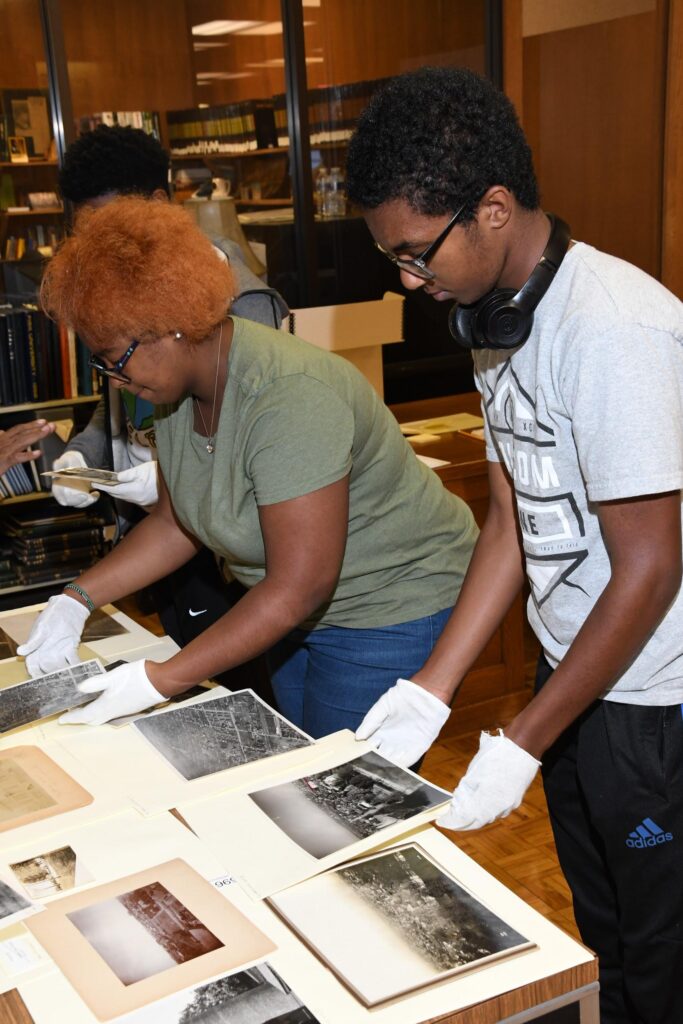

Student researchers participated in HRPG-supported projects in different, sometimes multiple, ways at different institutions: as part of a methods-focused undergraduate course, as an independent study for credit, as interns during the summer or semester, as paid research assistants, or as work study students in a campus library. Whatever the formal arrangement, the students dedicated intensive and focused time to investigating and interpreting primary source materials. They also developed new skills while producing videos and podcasts, creating posters and exhibits, applying digital mapping tools, coordinating in-person events, writing blog posts and exhibit labels for public audiences, etc.

For many students, the most significant impact of the public humanities work was an opportunity to delve deeply and thoughtfully into subjects that felt personally meaningful and relevant to them. Dana Winters, formerly executive director of the Fred Rogers Institute at Saint Vincent College (PA), observed that her “students found the ability to drive their research to be a fulfilling experience, one that was unexpected as undergraduate students. … [They] had the ability to define their own connections between their research, the archival items, their school, and broader communities. Not only did this create a strong buy-in for the students, but they also demonstrated higher than expected levels of engagement and pride with the process and outputs of the project.”

Some students forged a personal connection while being introduced to unfamiliar topics; others explored familiar subjects in new ways or settings. Consider the students from Champlain College (VT), who explored the impact of urban renewal on the surrounding city of Burlington, especially the displacement of residents from the local “Little Italy” during a wave of mid-20th century redevelopment. Twenty-four students worked over two semesters with a local historic preservation group, Preservation Burlington, to create a podcast and video documentary. They also captured and shared the sights and sounds of present-day neighborhoods through photographs and audio recordings. At the end of the project, one student reflected that “it was a really great thing to be involved in to learn more about my new community and gain an understanding of local politics.”

Being engaged and informed about what is happening in the community I live in is really important to me and being a college student in Burlington I am significantly removed from what the everyday life of someone living here may be, or the long-term shifts and changes and problems the community has been facing ... I [now] feel so much more informed about local issues and have a better understanding of the city as a whole.

Another student, who was concentrating in sound design, reported that the project “opened me up creatively, it illuminated for me some of the local politics of Burlington, and it prompted me to think more deeply and pay more attention to the sounds around me.” A third student reported that it was “fascinating learning about the immigrants who moved to Burlington and how their cultures affected the development of the city. My favorite part of the project … was learning more about the city that I thought I knew so well.”

The HRPG-supported projects challenged students’ research skills and pushed them to share their interpretations and conclusions in non-traditional academic formats including videos, podcasts, and exhibitions. At Bethany College (KS), for example, the project team worked closely with staff members from a local historic site (the Lindsborg Old Mill and Swedish Heritage Museum) to research local immigration histories and produce short videos for the public. In the process, the student researchers absorbed many lessons about the complicated, unpredictable, time-consuming, yet deeply rewarding nature of archival research for public engagement:

[The students who were] responsible for locating archival material discovered just how difficult this task can be, especially without a professor nearby to help. It was a crash course in learning the tenacity and inventiveness that researchers must have to be successful. For the second group of students responsible for creating a narrative for a visual medium, the difference between creating a product for a general audience as opposed to a scholarly audience proved challenging. The classroom has stressed the importance of scholarly work, both in terms of analysis and documentation, that is often cold and detached, but students quickly discovered that creating a compelling narrative for a non-academic audience required a more “artistic” bent than they previously expected.

Student researchers from Saint Mary’s College (IN) reached a similar conclusion while completing a project on humanitarian work with refugees and displaced persons performed by the Sisters of the Holy Cross in the 19th and 20th centuries. One Saint Mary’s student said that she “recognized there were higher stakes in my writing since what I produced would be shared publicly. There is a major difference between writing for a grade, a limited and known audience, and writing for the public, an unknown audience. … I put more thought into the public writing I did for this [methods] class than I would have if I were only writing it for a grade.” Another reported that “despite the overwhelming amount of information, emotions, and time put into this project, the takeaway is quite simple: knowledge is power. … [W]e hold a substantial amount of power as seekers of knowledge.”

[Students] sharpened their academic skills as readers, writers, and critical thinkers, but also more personal traits related to communication and resilience.

The students from Saint Mary’s College were not the only ones who concluded that public-facing projects require an investment of time and energy that far exceeds the attention often paid to traditional courses—a recurring theme in the evaluation reports filed by the HRPG grant recipients. But the opportunity to share their findings with community members made the extra work worthwhile. “Students took a lot of pride in the [final] project,” read a typical report from a campus team. “They were excited to go to the opening and closing events so that they could stand around the exhibit pieces and talk with community members.” Students were asked to work individually and collectively to strategize and solve problems, then share their research findings with both peers and strangers; in the process, they sharpened their academic skills as readers, writers, and critical thinkers, but also more personal traits related to communication and resilience. The benefits of public humanities work are not, therefore, limited to students with the strongest (traditional) academic skills: as one archivist observed, “I have seen students who failed the Intro to Freshman Lit class and had to take it remedially over January be fascinated by archival things and be engaged with them.”

For some students, working on HRPG-supported projects opened new career possibilities. Some were exposed to the professional work of archives and museums for the first time, either on campus or at significant cultural organizations off-campus. Students from Franklin College (IN), for example, got to meet with staff members from the Indiana Historical Society, who described the various professional roles in archives, libraries, museums and galleries. At the end of the visit, one student asked, “what kinds of training and education do you need to do this kind of work?” At Simmons University (MA), students worked with a local museum in Boston to create an online exhibit drawn from the archival records of an early 20th-century settlement house; by the end of the year, the project team reported that a quarter of the students had decided to pursue graduate study in archives/library science or seek a related career in the public humanities. Simmons may be exceptional, given the prominence of its own library school, but other HRPG teams also shared good news about individual students who were planning to pursue a previously unexpected graduate degree or career.

Other reports from the project teams focused on specific career skills. “[Our project] helped [students] find their interest in archives and digitization,” reported one faculty member. A student concurred: “[my new and] marketable skills in archiving and digitization…put me ahead of my undergraduate peers. … [T]his project is the primary reason I was able to land a collections internship this summer. I learned how to work with and train other students, and I’ve even taken a tentative step into curation and exhibit text writing.” Other students expressed a general appreciation for the public humanities skills they could now put on a resume or in a portfolio: “I know that the skills I have learned will be a real leg up in law school and later on. I just used this project to apply for a summer research program [at a law school].”

Students and their faculty mentors also commented on the general professional skills—such as teamwork or writing and speaking to diverse audiences—that had been strengthened by participating in a public humanities project. One faculty member focused on the “team meetings that [student researchers] attended with different administrators and campus leaders. That was new for them, with an agenda and the whole bit, coming prepared. Those sorts of things I think were really, really helpful … [and] really set them apart.” Another faculty member, from another campus team, concluded that “the professional development that they got alongside [the academic work on the project] was pretty immense. They did several presentations in front of different audiences. Navigating how to make a presentation on the same content but for different purposes was useful. … They wrote reflective pieces, they wrote thank-you notes, they wrote invitations, all kinds of different things. … [T]hey learned new technology that they had to then use.”

Faculty Members

In order to reap all the student benefits described above, publicly engaged humanities projects require a strong infrastructure and a distinctive pedagogy to support students as they test new forms of learning. Most of the student research for HRPG-supported projects was embedded in special topics and methods courses or facilitated through summer internships and research assistantships. Faculty members discovered, however, that more rigorous scaffolding was required when it came time to guide students through publicly engaged, project-based, collaborative community projects. The infrastructure for public humanities work needs to address a challenging constellation of research and communication skills, a variety of supportive and productive relationships, and the public accountability demanded by public-facing projects. At the same time, educators need to reimagine their roles and expectations to include project management and coaching, in addition to teaching disciplinary content and research methodologies.

According to many reports from participating faculty members, the HRPG-supported projects increased both the quality and quantity of their interactions with students and colleagues alike. Many faculty members also discovered that public humanities projects shifted how they saw their role in the traditional classroom. One wrote that

It felt more like a coaching kind of gig than a professor-type gig, in that there were moments of encouragement, there were moments of reputation management ... [and] conversations about how to engage with certain audiences. ... [We had] to take the project in ways that I wasn’t anticipating, sometimes with really amazing results.

Another explained how working on a public project and with community partners transformed the entire learning context: “I was no longer the one with the information; the community was. I was just the intermediary, stepping back, but also an intermediary between other faculty members [in other departments] because then we started to see connections [between disciplines].”

While the chance to make an impact on students and communities was a source of satisfaction, the HRPG-supported projects still challenged faculty members with increased workloads and new demands for public accountability. Many struggled to find sufficient time to devote to their projects; nearly every faculty member, and most collections specialists, said that the projects took more time and effort than they expected. (One faculty member thus advised others in her shoes to seek a course release to help “level up the project”—especially when trying to tie public-facing activities to departmental requirements.) One response was to think more strategically about gathering resources that could be used for both present and future projects. Several teams, for example, adopted a “train-the-trainer model,” relying on more experienced students to support their peers: “I tried to embed certain parts of the project in my public history class,” reported one faculty member, “even if they were just observing, to kind of help manage my time but also share resources and give students more opportunities to [contribute].”

It [was] difficult to strike the right balance between student-driven projects … and public-facing projects.

According to many faculty members, the collaborative nature of the HRPG projects made it difficult to strike the right balance between student-driven projects—in which students directed the research questions and maintained control over the public projects—and public-facing projects that required more direct control by faculty members, archivists, and community partners. At Lewis & Clark College (OR), the campus team developed a series of podcasts about the local Vietnamese community, drawing from an ongoing oral history project. Two students worked intensively (but somewhat autonomously) over a summer and academic year to research, write, and record the podcast episodes, in consultation with faculty members and representatives of a community nonprofit. At project’s end, the primary faculty member on the campus team reflected on the process:

The faculty and staff members involved in the project ... might have exerted more editorial control over the content of the podcast, although in the end we felt it was important that the students make their own decisions. Some of us had expected a more journalistic approach, in which a handful of lives or experiences were explored closely and the students did supplementary interviews and additional research in directions we hadn’t previously considered. Instead, the students took a more historical approach, trying to tell an overarching story about the Vietnamese community’s history in Portland. They managed to pull this off respectably, and in any case it was clearly beneficial for the students to pursue their own vision.

This particular challenge could be addressed through project design and internal processes that strengthen the scaffolding that supports student learning, or providing additional layers of editorial review. Ultimately these are educational projects, so it is important to let students make mistakes and to work through problems without abandoning oversight, while still ensuring that projects are adequately completed and the expectations of community partners are met.

Archivists and Special Collections

The HRPG-funded projects focused on identifying materials in archives and special collections libraries that could be used to expand public understanding of community history, prompt new ways of thinking about the present, or inspire new visions of the future. The range and types of archival collections that were employed reveal some of the riches housed in small college libraries:

- Botanical watercolor paintings

- Audio recordings of poetry readings by renowned authors

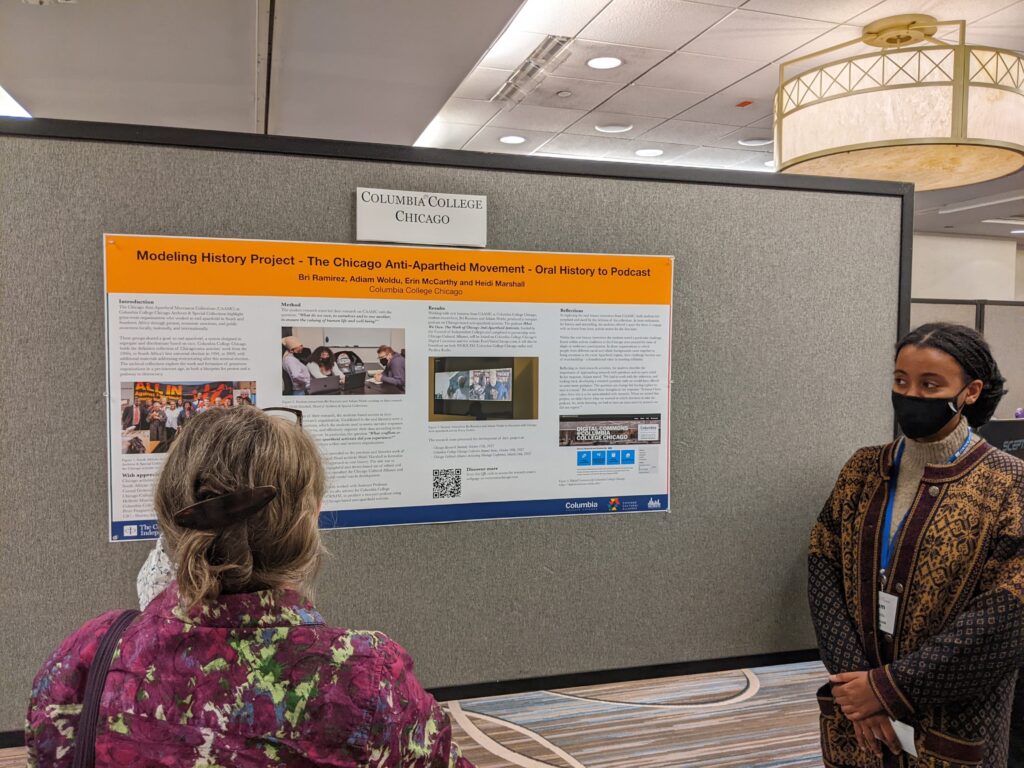

- Oral history interviews with anti-Apartheid activists

- Historic collection of sex education pamphlets

- 1960s snapshots from a community roller rink

- Early 20th-century sheet music

- Personal papers of Fred Rogers

- 1847 Bible census of Washington, DC

- 19th-century missionary scrapbooks

- Settlement house records from Boston

- Public papers of Indiana Governor Roger D. Branigin

In addition to highlighting unique collections, HRPG funding was a stimulus to explore how specialists in primary source materials—archivists, librarians, curators—can support the academic work of students and faculty members, or even to reimagine the relationship between special collections and classrooms. Campus archives and special collections can make important contributions to colleges’ and universities’ educational activities when they have sufficient resources and when they are recognized as repositories of significant research and teaching materials. Similarly, archives professionals are eager to feel respected as colleagues and to play a recognized part in colleges’ educational missions.

The role played by archives and special collections differs from campus to campus, as does each library’s strengths and resources. But most collections professionals (including the archivists who participated in the HRPG-supported projects) agree that special collections are undervalued and underused. In part, this is a matter of resources. It can also be a matter of perception: some administrators and faculty members, especially at teaching-focused institutions, view special collections as a luxury or an “institutional vanity project,” with little direct impact on students. One archivist (re)stated their commitment to “institutional archives and libraries [as] a way for us to build knowledge together. That’s the really exciting thing, in that universities are supposed to be places where knowledge is exchanged and grown and shared, and that the archives is supposed to be the key place where that happens.” Because of budget cuts and increasing workloads, it has become harder for archivists and librarians to demonstrate how they contribute to student learning on campus. Participating in an HRPG project, on the other hand, “was a chance to say that archives are pedagogically useful, that they do provide an opportunity for students to have something hands-on….[I]t also gives them the sense that they can contribute to history, that they can be empowered to do that.”

The funded projects drew upon archival materials in various ways. At many of the participating institutions, students became producers of collections by conducting oral history interviews or making existing materials digitally accessible. These activities exposed student researchers to the behind-the-scenes work of collections professionals who compile metadata, prepare finding aids, and preserve both physical and digital materials. The hands-on work of making archival materials accessible also inspired students to think more critically about the role of archives in the production of knowledge—and the place of knowledge in their own lives. An archivist on one campus recalled that students had outdated preconceptions about archives; working on public humanities projects gave them new frameworks for thinking about original sources. Although they enjoyed exploring old paper documents, the students found it especially intriguing to learn “that archives can be born digital, and moving forward they probably increasingly will be.” By considering a broader array of evidence that might be archived, students realized the relevance of archives in their own lives; the public humanities work forced students to “really reflect on their own digital footprint and the idea that it is something that is preservable.”

[The HRPG projects] inspired students to think more critically about the role of archives in the production of knowledge—and the place of knowledge in their own lives.

The impact of an institutional repository on student learning depends on both the professional expertise of the archivists/librarians/curators and their effectiveness as educators. The HRPG projects provided opportunities for collections staff to be active collaborators in authentic student and faculty research, beyond just responding to researchers’ requests or making special collections accessible to students. The grant guidelines required each institution to include a collections professional as a full member of the project team, which increased the length, depth, and nature of archivists’ involvement in research:

Generally, we host students and share materials and information with them and assist in deepening their engagement with the materials, the process, and the content for better research. These grants permitted much more student involvement with primary materials than just a few hours of time—[and] the grants allowed for a deep dive into the history and the ‘guts’ of collections in ways that are not generally made available to archives staff. ... [Instead] archives staff working side-by-side with faculty and students over the course of a project allow[ed] for levels of engagement not usually experienced by staff and ... made the process more meaningful when all parties were involved throughout the entirety of the project.

One archivist characterized their role in the project as “Archives 180°, where you’re turning it around”—for example, by taking the lead in identifying special collections that could be at the center of a public-facing project. Another archivist described a similar spin: “[I]t was unique for me in that I was going to students with an idea and saying, ‘here, I want you to research this.’” The archivists who participated in a post-project focus group were eager to continue this level of deep engagement; they wanted to keep “building knowledge that had not previously existed.”

Just as the faculty members on the teams discovered, expanding the role of the collections specialist brought an increased workload. To help ease this additional burden, archivists pointed to the importance of coordination and good communication within campus teams and with community partners. For their part, many faculty members observed that working closely with their library or archives colleagues on HRPG-funded projects increased their respect and appreciation for collections specialists. One participant wryly explained that the faculty members on his campus came to realize that archivists are not “magical flight attendants” who can immediately deliver materials; with the right resources and recognition, they could play a larger role in delivering the college’s educational mission.

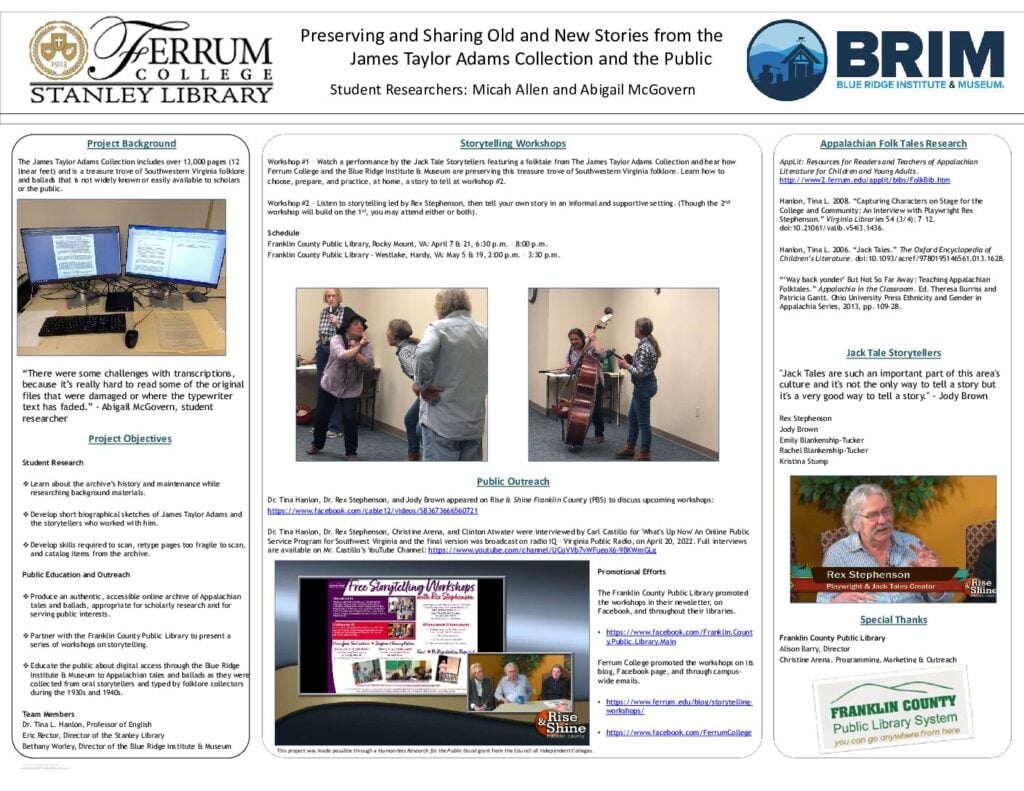

The collections specialists also brought an important perspective to the entire HRPG initiative, by reminding their campus colleagues and the CIC staff about the importance of preserving both the research materials and the public-facing materials generated by any public humanities project. Many of the materials generated by public humanities projects—digital exhibits and websites, oral histories, syllabi and lesson plans, podcasts and multimedia presentations—as well as photos and videos of community events and even surveys completed by audience members can be preserved to provide future materials for researchers, students, and community members to explore. However, it is essential to plan for digital preservation from the outset. (To our chagrin, the CIC project staff did not develop such a plan until very late in the process—too late to capture some of the excellent work done by HRPG grantees in 2019–2020.) This will ensure that a project team has the necessary resources and skills for digital preservation, can develop an appropriate workflow, and can identify an appropriate platform to store, conserve, and share materials. According to a survey of HRPG grant recipients, most of the participating institutions (about 80 percent) had a plan and infrastructure in place to maintain digital access to project materials for a reasonable amount of time; the most significant barriers to implementing their plans were funding and staffing. In response to these survey results, CIC offered a supplemental round of small digital preservation grants. A more sustainable solution may be shared repositories, such as the Digital Library of Appalachia (where Tusculum University (TN) has deposited a collection of oral histories and Appalachian folktales) or Ohio Memory (where Defiance College (OH) has deposited a collection of digitized materials related to the state’s immigration history).

Society of American Archivists Award

Colleges and Universities

Public humanities projects prosper when they align project goals with institutional goals. When HRPG teams linked their projects to broad institutional missions and strategic plans, or to specific current initiatives, they benefited from access to resources and infrastructure to support the students’ work. The original call for grant proposals tried to institutionalize this alignment by requiring each team to include an academic administrator (such as a provost or division dean)—but everyone soon learned that it took more than just having an administrator on the team.

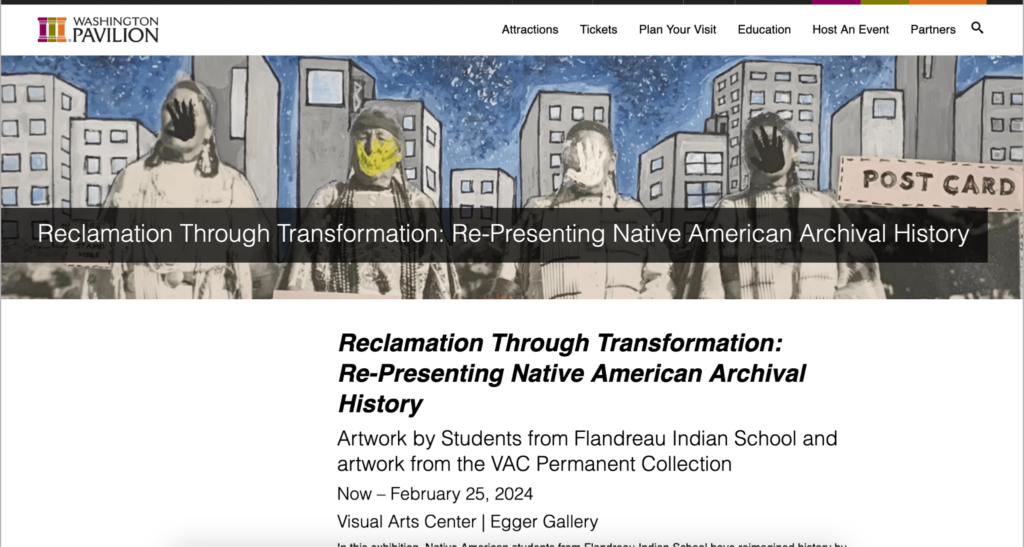

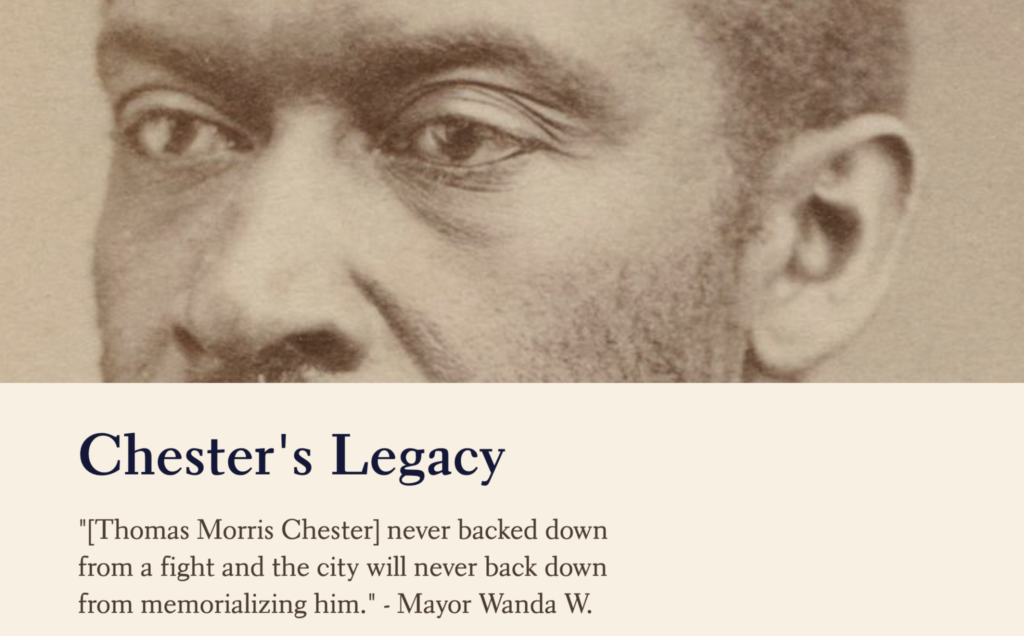

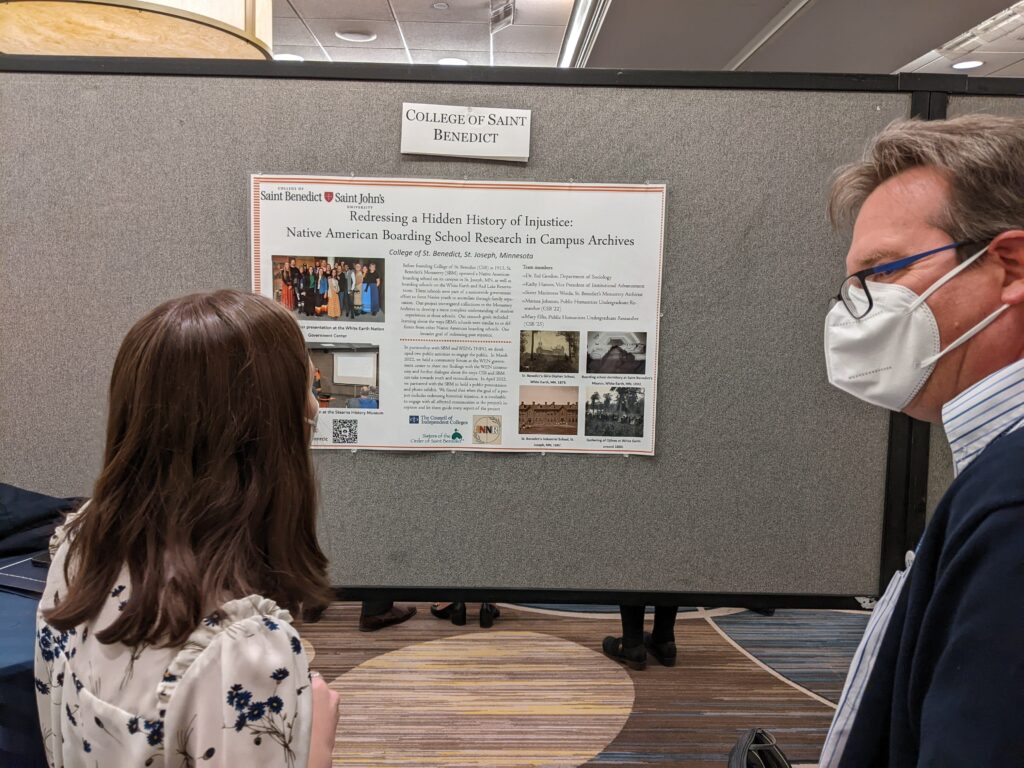

At some institutions, the HRPG-funded projects were linked to ongoing efforts to investigate difficult institutional histories that had been ignored or suppressed in the past. The project team from the College of St. Benedict (MN), for example, benefitted from an evolving relationship with the nearby White Earth Nation; as the HRPG team used archival research to explore the history of Native American boarding schools, they contributed to an ongoing truth and healing process while sharing their findings with tribal leaders. The project team from Augustana University (SD), in collaboration with a local arts venue and students from the Flandreau Indian School, also focused on the painful history of Indian boarding schools—a history that deeply implicated some of the university’s founders. At Wofford College (SC) and Goucher College (MD), the HRPG-funded projects supported existing initiatives to reckon with the histories of slavery and race on these campuses.

Some teams explicitly linked their HRPG-supported projects to mission-driven student outcomes. For example, the projects at Bethany College (KS), Defiance College (OH), and elsewhere sought to increase students’ knowledge of diverse cultures through projects focused on immigration; the projects at Oberlin College (OH), Saint Mary’s College (IN), and the University of the Incarnate Word (TX), among others, supported institutional commitments to social justice by exploring histories of social justice activism. Many teams used their projects to focus attention on the role of the college or university in the local community, prompting students to think about the relationship between the campus and the community, today and in the past. See, for example, the community-focused projects from Berry College (GA), Bushnell University (OR), Connecticut College, Daemen College (NY), Fisk University (TN), Franklin College (IN), George Fox University (OR), Messiah University (PA), Saint Peter’s University (NJ), Springfield College (MA), Thiel College (PA), the University of Findley (OH), and Washington & Jefferson College (PA).

Other campus teams connected their project work to new academic priorities, including new subject areas and new initiatives to support student career development. At Carlow University (PA), for example, the HRPG project team explicitly aligned their investigation of a literary archive (the International Poetry Foundation, or IPF) with the university’s mission and strategic plan:

Carlow’s mission prioritizes “transformational educational opportunities” for a diverse community of learners to empower them to excel professionally as “compassionate, responsible leaders in the creation of a just and merciful world.” Learning about the IPF writers’ commitment to social justice reinforced the university's commitment and provided models for compassionate, responsible leadership.

As noted above, the HRPG-supported projects almost always incorporated high-impact teaching and learning practices. In some cases, they also served as practical demonstrations of experiential learning, applied research, and digital humanities on campuses where these pedagogical approaches are atypical. The HRPG team at Saint Mary’s College (IN), for example, reported that their 2019–2020 project “demonstrated to us [and our colleagues] that it was possible to successfully develop a curricular ecosystem that allowed for the coordination of multiple classes [that contributed] to a public and/or digital humanities project from various angles.” To address the challenge of coordinating multiple courses and separate groups of student researchers, the college launched a new minor in digital and public humanities. The new structure should make it easier to develop collaborative project-centered classes while highlighting student-faculty research (a “signature component” of the curriculum) and preparing students for meaningful career opportunities.

In addition to any specific contributions to an institution’s strategic plan, curriculum, or career preparation efforts, public humanities work can help shift the perceptions that campuses and communities have about each other. Public engagement can, of course, take many forms, from inviting community members to enjoy campus spaces and programs and encouraging students and staff to become involved in community-based organizations to the co-creation of knowledge and programming represented by so many of the HRPG-funded projects. Across the board, HRPG-supported projects helped generate positive publicity for the institutions involved (the list of funded projects includes several links to media coverage). As one faculty member explained, the “better brand awareness” subsequently benefited “our students who are going out for internships and stuff in the community”:

All of a sudden the students and the community understand that we [the college] are not here as the white savior to hear what you’re missing and then give it back to you but rather we want to learn from you—you are our teachers now, not the other way around—that was very helpful to create a better bond with people in our community.

Community Partners

As campuses work to broaden the ways they connect with meaningful communities—especially communities defined by geography—they also have an opportunity to redefine scholarship to include collaborative knowledge creation and community-based projects that address local concerns. Public humanities projects are a chance to rethink the role that community institutions and community members play in the life of a college or university, by inviting them into campus spaces where they can share experiences and expertise.

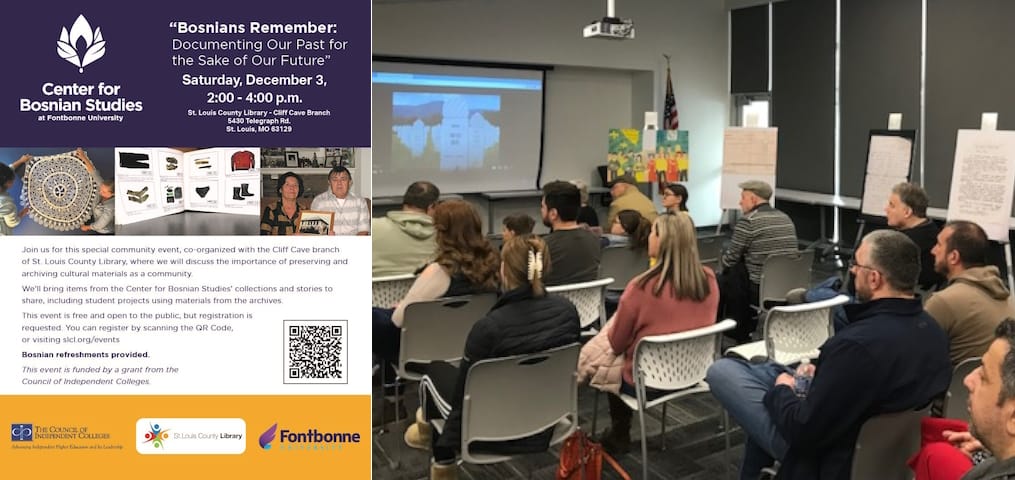

All of the HRPG project teams embraced a spirit of public engagement and a desire for their work to result in a public benefit, while embracing different definitions of the “public good.” For some teams, that meant producing public events, hosted by public libraries or historical museums, that contributed to a partner’s public programming and extended the college’s outreach to new audiences. The partnership between Doane University (NE) and the Spring Creek Prairie Audubon Center, for example, led to a public exhibit at the nature center where audiences could view historic watercolors that depicted the area’s prairie ecology as it appeared in the late 1800s. A partnership between the University of Denver (CO) and the local public library was leading to a library exhibit and conversation about the history of public health in the city and the contemporary health landscape; ironically, the exhibit had to be cancelled at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic but was transformed into a robust digital presentation on the websites of both institutions.

All of the HRPG project teams embraced a spirit of public engagement … while embracing different definitions of the “public good.”

For other teams, the public good was served by researching topics that could answer questions of pressing concern and real interest to their partner organizations. The project team from the University of the Incarnate Word (TX) exemplified this approach by partnering with a local housing advocacy organization to offer workshops about housing justice in San Antonio, inspired by historical examples from the institutional archives of community-based social work performed by the Sisters of Charity. In Chester, Pennsylvania, students and faculty members from Widener University teamed with Women Organized Against Rape to develop a public education program about sexual consent that included an analysis of the history of social norms related to sexual consent, drawn from materials in Widener’s Human Sexuality Archives. In rural Tennessee, Tusculum University partnered with the Rural Resources Farm and Food Education Center to explore generational change in the local community, combining the historical analysis of archived interviews from the 1980s with a new oral history program, a community picnic (complete with food inspired by family recipes), and an exhibit of historical photographs.

Some of the colleges and universities struggled to find community partners that had the resources and the enthusiasm required for successful collaboration. Saint Peter’s University (NJ), for example, initially partnered with a local Metropolitan AME Zion Church for a community memory project examining the city’s African American history. The church famously hosted a 1968 visit to Jersey City by Martin Luther King, Jr., and continues to play a significant role in the community. Unexpected personnel changes made it hard for the church to meet its commitment to the project, however, and the Saint Peter’s team had to scramble for a replacement: the Monumental Baptist Church. This revitalized the entire project as the new partners combined to plan an outdoor festival for community members that also showcased the students’ research. After an initial setback, “we broadened the scope of our public engagement [and] found a more engaged community partner. … As our community partner, Monumental Baptist Church [became] an enthusiastic collaborator in this project. They have connected us to church elders who are eager to share their stories, and they took the lead in organizing [the outdoor festival].” Ultimately, the Saint Peter’s team concluded that “an engaged community partner is vital for the success of a publicly engaged project.”

It can be difficult to measure or even see the impact of a publicly-engaged humanities project. Many of the HRPG teams struggled to evaluate the outcomes of their work, but they did gather basic evidence of reach—e.g., the number of attendees at events or the number of clicks on web-based materials—and they documented in-person activities by taking photographs or recording videos. The team from Daemen College (NY), a predominantly white institution in the suburbs of Buffalo, diligently recorded the number of viewers, clicks, and comments on a website devoted to the Skateland Project, an archive of snapshots documenting fun times at a defunct roller rink in a predominantly Black neighborhood near the campus. In their final report to CIC, the Daemen team shared two important reflections about the limits of relying on such analytics to measure the impact of their project. First, they quickly realized the need to connect with people face to face in order to generate visits to the website:

As we reflect on the outcomes of the Skateland Project we consistently return to the word JOY. The joy came through the happiness expressed by the people in the photos. The joy came through the levity in the voices of the people sharing stories from their childhood. The joy came through individuals who had their memories sparked as they remember years gone by. No one was unaffected by the joy expressed in these photos.

As Daemen’s team learned, publicly engaged humanities projects do not automatically or inevitably result in meaningful outcomes. Positive benefit requires thoughtful design, consistent communication with partners, and absolute commitment to following through on promises made to collaborators. As another participating faculty member warned, “There’s a real challenge with that, especially when you seek to do these types of community engagement, relationship-building partnerships, where the person who was really selling something to neighbors just disappears. The only thing worse than not engaging a neighbor at all is to pretend like you’re going to and then just vanish. That really sets up this reputation that you’re not to be trusted.”

Final Thoughts

Humanities Research for the Public Good was a limited initiative, despite the generous support of the Mellon Foundation. CIC is proud of the impact that relatively small project grants could make in the hands of dedicated faculty members, collections specialists, academic administrators, students, and community partners. Their experiences make clear the many ways that publicly engaged humanities research can yield immense rewards for project teams, their communities, and the colleges and universities that incubate and support such projects. Sustaining the work and its impact is now largely the responsibility of the individual institutions. Indeed, one success of the HRPG initiative is that many colleges who benefitted from participation have continued their support for the public humanities, building on the lessons of the funded projects and the local infrastructure and partnerships that grew out of the earlier work.

The HRPG project teams have been generous in sharing their experiences and practical advice through formal workshops, an informal community of practice, and evaluation tools. Just some of their wisdom is included in this report, which we hope will nonetheless be inspiring and instructive for other institutions.

Here are a few final keys to successful and sustainable work in the public humanities:

- A strong project team that understands its strengths and limits and is willing to learn and listen and, when needed, to correct course, change direction, and/or seek out additional team members.

- A clear understanding of your audience(s).

- A research question that is interesting to students and relevant to members of the community.

- Community partners who are willing and able to enthusiastically contribute to a project.

- An eagerness to build new relationships off campus and the hospitality to welcome more members of the community to your campus.

- A plan to document and preserve a record of your project.

- Institutional support, in both tangible and intangible forms. (This might include: a course release for faculty members; stipends for archivists or other collections professionals when their work on public-facing projects goes beyond their formal job descriptions; a development or grant officer whose brief includes grants for humanities research; flexible classroom assignments that recognize multiple ways that students may demonstrate learning; faculty evaluation procedures for promotion and tenure that recognize publicly-engaged projects as a form of research, and much more.)

- A sense of humility and a sense of responsibility, especially in your interactions with members of the community beyond your campus walls.

Full List of Projects

Digital Preservation Grants

In 2024, CIC awarded additional grants to 13 institutions to support digital preservation and/or public access to materials that were created or utilized as part of an earlier grant-funded public humanities project:

- Butler University (IN)

- Connecticut College

- Defiance College (OH)

- Doane University (NE)

- Fisk University (TN)

- Fontbonne University (MO)

- Franklin College (IN)

- George Fox University (OR)

- Lewis & Clark College (OR)

- Messiah University (PA)

- Rust College (MS)

- Saint Mary’s College (IN)

- Saint Vincent College (PA)

Project Publications

Artman, Margaret, Elizabeth Campbell, and Kristen Luppino-Gholston. “Collaborating to Build a Successful Interdisciplinary, Community-Based Project.” College Teaching (February 2022). Based on the HRPG-funded project at Daeman College (NY) in 2019–2020.

Crummé, Hannah Leah. “Building Community Archives: Vietnamese Portland,” in Daniel Fisher-Livne and Michelle May-Curry, eds., The Routledge Companion to Public Humanities Scholarship (New York: Routledge, 2024), pp. 128–138. Based on the HRPG-funded project at Lewis & Clark College (OR) in 2019–2020.

Dickson Chloe, and Anna Strange. “Student Voices: The Commonwealth Monument Project.” Humanities for All Blog (November 17, 2020). Reflections on the HRPG-funded project at Messiah University (PA) in 2019–2020.

Farley Lisa. “Finding Etheridge Knight: A Case Study on a University’s Public Humanities Project.” Collaborations: A Journal of Community-Based Research and Practice 6:1 (2023). Based on the HRPG-funded project at Butler University (IN) in 2019–2020.

Harris Alea, et al. Acknowledging Our Past: Race, Landscape and History (Wofford College, 2020). A collection of essays produced by student researchers as part of the HRPG-funded project at Wofford College (SC) in 2019–2020.

Mannon, Ethan, and Karen Paar. “Influence and Legacy: The Farmers Federation in Madison County, NC.” Appalachian Curator 2:2 (Fall 2020). Based on the HRPG-funded project at Mars Hill University (NC) in 2019–2020.

McCarthy, Erin and Heidi Marshall. “The Columbia College Chicago Oral History Model in Action: A Case Study.” (August 2022). Based on the HRPG-funded project at Columbia College Chicago (IL) in 2021–2022.

Merchant, Abigail. “Student Voices: Spirits of Pine Log Mountain.” Humanities for All Blog (November 17, 2020). Reflections on the HRPG-funded project at Reinhardt University (GA) in 2019–2020.

Merikalio, Caitlin. “Student Voices: The Oberlin Sanctuary Project.” Humanities for All Blog (November 17, 2020). Reflections on the HRPG-funded project at Oberlin College (OH) in 2019–2020.

Pennsylvania History 87:1 (Winter 2020). Special issue devoted to “Harrisburg, Digital Public History, and the ‘City Beautiful,’” featuring research by students and faculty at Messiah University (PA) that was supported, in part, by HRPG funding.

Powers, Peter K. “How to Institutionalize Public Humanities Projects.” Public Humanities 1 (2025): e46. A version of the remarks that Dr. Powers presented at the HRPG workshop in April 2020.

Williamson, Laura. “The Displacement Project: Archival Storytelling and the Sisters of the Holy Cross.” Humanities for All Blog (October 18. 2023). Describes the HRPG-funded project at Saint Mary’s College (IN) in 2019–2020.

Credits

Humanities Research for the Public Good was generously supported by a grant from the Mellon Foundation with supplemental funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities through the CARES Act. The findings and opinions contained in this report are not necessarily those of the Mellon Foundation or the NEH.

This report was prepared by Anne M. Valk, who served as director of the Humanities Research for the Public Good program, with Philip M. Katz, senior director of projects at CIC. Valk is professor of history and executive director of the American Social History Project/Center for Media and Learning at the CUNY Graduate Center. Valk is a specialist in oral history, public history, and the social history of the 20th century United States. She previously served as associate director for public humanities at Williams College (MA), deputy director of the Center for Public Humanities at Brown University (RI), and director of women’s studies at Southern Illinois University Edwardsville. She has also served as president of the Oral History Association and is book series editor of the Oral History Series published by Oxford University Press. Katz is a prize-winning historian who previously worked for the New York Council for the Humanities, American Historical Association, and American Alliance of Museums.

Finally, CIC would like to thank the following people who served as workshop presenters in 2019–2022 (affiliations at the time of their presentations):

- Edward L. Ayers, President Emeritus, University of Richmond (VA)

- Christy S. Coleman, Executive Director, Jamestown-Yorktown Foundation

- Stephen Kidd, Executive Director, National Humanities Alliance

- Modupe Labode, Curator, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution

- Sheri Levinsky-Raskin, President, SJLR Solutions; Former Assistant Vice President for Research and Evaluation, Intrepid Sea, Air & Space Museum

- Jo Ellen Parker, Senior Vice President, CIC; Former President, Sweet Briar College (VA); Former President, Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh

- Peter Powers, Dean of the School of Arts, Culture, and Society, Messiah University (PA)

- Lynn Rainville, Director of Institutional History, Washington and Lee University (VA)