Reviewed by Ben Utter

Associate Professor of English, Ouachita Baptist University

There’s something more than a little ironic about leafing through a book entitled Deep Reading with anything like haste. Indeed, as the book’s subtitle suggests, a better word for hurried reading practices might be a “vice”! For those readers who can relate, Deep Reading’s call for reading practices that subvert superficiality and nourish substance may well be a restorative and useful pleasure. And although the book makes little use of the language of vocation explicitly, it emphasizes deep reading as essential for asking questions about the nature of “the good life”—a valuable practice for those of us engaged in helping our students reflect on their callings.

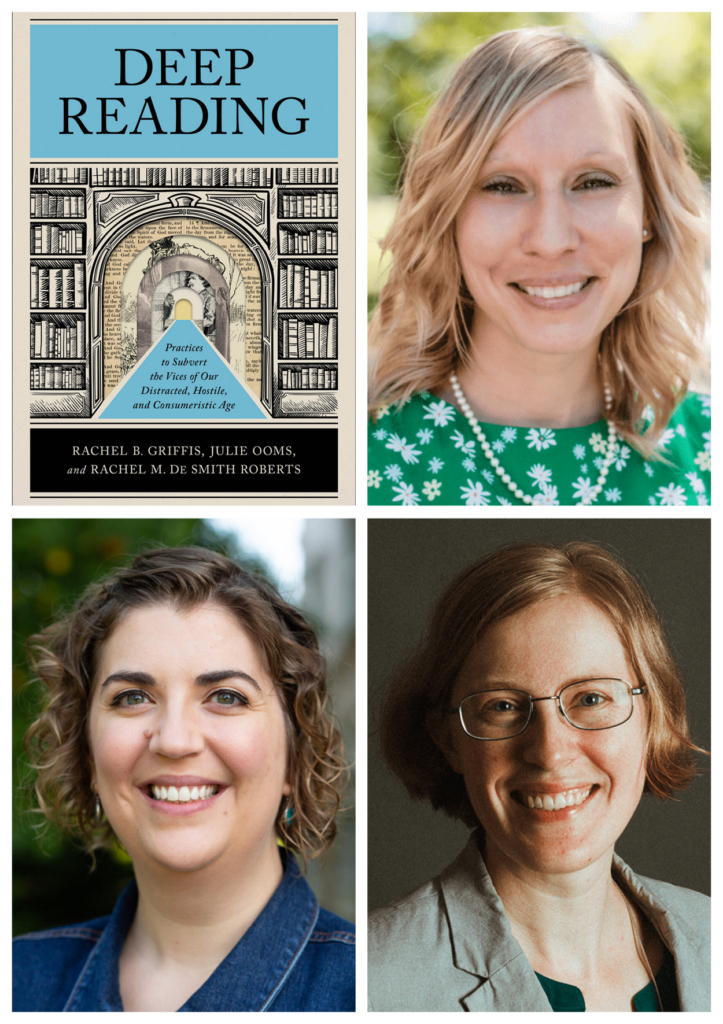

There has been no shortage of books on the threats that our era of digital distraction and discord pose to careful reading and thinking. But what Griffis, Ooms, and Roberts add to the existing literature is an emphasis on the cultivation of virtue. That might not sound particularly sexy—chapter one describes paying attention as an exercise in temperance—but their appeal to virtues such as humility, charity, generosity, leisure, and joy couldn’t feel more urgent or innovative, especially as a way to frame issues like teaching neurodiverse student populations and using digital reading tools equitably.

Deep Reading’s emphasis on virtue formation will look familiar to those versed in recent literature on vocation. More novel, though, is its presentation here as a counter to the growing focus on the teaching of a particular “worldview” in Protestant education—a teaching philosophy preoccupied with correct thought and belief. Framing education with respect to the virtues, this book argues, serves to remind us that what we do matters—just as much as what we think and know. This approach can also help students interpret worldviews rather than merely react to them. This process of interpretation is vital for effective vocational thinking and could be particularly helpful for those teaching and learning in Christian educational communities.

The authors’ own innovations are central to the book’s approach. Each chapter includes practical and, as they put it, “prudent” strategies—activities, rituals, and discussion questions—that cultivate deep and pleasurable reading. They make these suggestions not only for individuals, but also among communities of readers, whether old friends in a book club or first-year college students intimidated by a roomful of strangers. For instance, anyone whose spring syllabi or book club reading lists are going to feature older or “problematic” books would benefit from reading the chapter, “Inclusive Practices to Cultivate Listeners.” In it, Ooms describes how she teaches Huckleberry Finn and helps her students maneuver the novel’s representations of horrific racism with humility and curiosity rather than reflexive disdain. Drawing on what C.S. Lewis calls “chronological snobbery”—the attitude many modern readers feel toward anything deemed old and thus hopelessly unenlightened—Deep Reading argues that “we can develop productive, justice-oriented critiques of texts without sliding into chronological snobbery.”

Deep Reading went to press well before Percival Everett’s James—a remarkable retelling of Huckleberry Finn from the perspective of the enslaved Jim—was announced as this year’s National Book Award winner. But any lesson or discussion plans involving Everett’s novel would be similarly enriched by some of the “prudent reading” practices that the authors of Deep Reading propose. The prudent reader, they explain, is one who forgets oneself while reading, and by doing so subverts hostile, fearful responses to texts that might seem threateningly alien. Self-forgetful reading of this kind requires reading relationally rather than transactionally—no simple feat, since, in their explanation, transactional reading is a natural consequence of the social ills of consumerism and individualism. Deep Reading’s descriptions of these reading practices are not only lucid and interesting; they also pair well with challenging books and foster a greater appreciation for deeper meaning-making. Whether one is navigating the landscape of the American South through Twain’s nineteenth-century eyes or assessing the ethically and artistically complicated feat Everett is attempting in James, the cultivation of such virtuous reading strategies is essential for vocational exploration and discernment.

In the book’s conclusion, Griffis, Ooms, and Roberts make what just might be their most radical proposal: embracing the benefits of rereading, which they argue is an act of rebellion against the seductions of novelty and against the worship of utility and efficiency as the highest human goods. They don’t have an unkind word to say about end-of-year reading lists (something many of us may have indulged in, or been subjected to, this past December). But their warning against a transactional approach to what should be intrinsically valuable could serve as a gentle corrective or a source of comfort, respectively, for those of us already working on our new 2025 reading lists with either undue pride or dismay.

The dubious merits of textual accounting practices notwithstanding, Deep Reading would make a fine starting point for this year’s list—so long as we bear in mind its admonition that how we read is every bit as important as what we read.

Back to top