Reviewed by Louisa M. Ward

Dean for Spiritual Life and Campus Minister at Campbell University

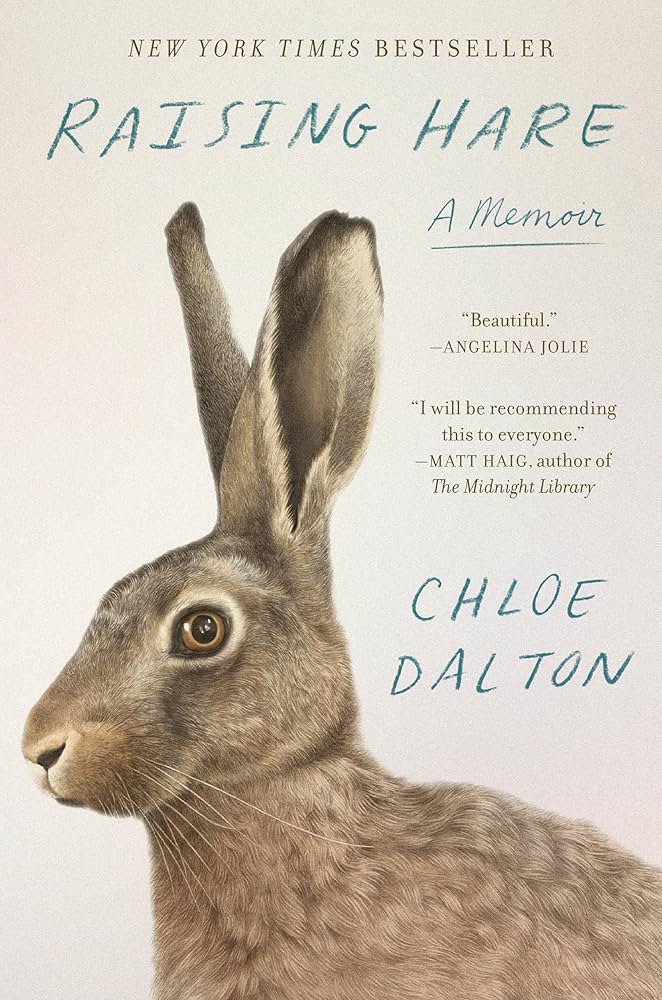

Extended stays at home during the Covid-19 pandemic were life-changing for us all. For Chloe Dalton, lockdown provided a companion and teacher she never saw coming: a leveret. She encountered this tiny hare on a walk just beyond the wall of her seemingly idyllic English countryside home. Designed by nature to blend in with its surroundings, the leveret is born an exact miniature of its adult self. Dalton’s leveret was nestled in the middle of the walking path, easily mistaken for a rock or small mound of dirt. It’s a wonder to me that she even saw the creature without stepping on it. Assessing her options, Dalton decided to pick up the animal, no bigger than the size of her palm, and take it home. From this moment on, nothing about the next three years of Dalton’s life was the same.

It wasn’t until I finished this gentle reflection on Dalton’s life with the leveret that I realized she had ultimately kept a record of a shift within her own vocation. The leveret she is determined not to name inspires a desire in her to be present to, to protect, and to care for another creature in a way she has never felt called to do before. She does not use the language of purpose, calling, or vocation in her attention to these subtle shifts, but anyone who knows the sacred task of being present with college students as they discover who they are, and who God is calling them to be, will hear this echo throughout her book.

I was surprised to find these themes beautifully woven into a book that has nothing to do with ministry or work in higher education, but once I started reading it as a comparison of leveret and college student, I couldn’t see anything else. For example, Dalton quickly learns that the leveret would not tolerate life in a cage. Limiting the leveret’s space caused it almost immediate distress, even though the intent was to keep it safe. This feels true in my work with college students. For many of the students with whom I have spent significant time over the years, adolescence was a time of neatly boxing into tidy compartments their understanding of God, their knowledge of scripture, and how they see themselves and others. This can be developmentally helpful, but it does not always serve students well once they reach college and begin asking questions and seeking answers—particularly in a community where we believe there is no conflict between a life of faith and a life of inquiry. As many have discovered, there is very little that is neat or tidy about the way God works in scripture or in the world. For some students, this messy revelation is disorienting. Yet, for others, the permission to stretch—both physically and theologically—is a freedom they didn’t know they needed in order to flourish.

In the same way that Dalton learns the leveret should not be caged, she also learns to let the leveret explore its “home range,” which, according to Dalton, spans fifty to four hundred and seventy acres (127). This home range included Dalton’s house, but once the leveret reached adolescence, it was ready to leap beyond the garden wall into the fields surrounding her home. Dalton recounts the exact day and time she watched the leveret pause on the garden wall before hopping over and out of sight. Her protector’s instincts immediately kicked in. What if the leveret got lost, or never came back? Would the leveret be accepted by the other more “wild” hares? What if the leveret was hurt while exploring? Of course, the leveret returned within several days, bounding back into the garden as if leaving to explore the fields beyond was the most natural thing in the world. For the students in our care, watching as they leap beyond the garden walls of even our own campuses is bittersweet. Yet, this is the most natural thing in the world.

In a more humorous, but equally insightful comparison, Dalton recounts the leveret’s response to a new living room couch. Upon returning home and finding the new couch, the leveret refuses to come into the house. Instead, the leveret sits on the threshold of the front door and stares suspiciously at the couch and then at Dalton. It takes Dalton several days to decide to put the old couch back in the living room for the sake of the leveret. As soon as she does the leveret comes into the house as if nothing has changed, bounding up and taking its place on the arm rest of the “old” couch. How many times have you moved the vocational furniture around so a student can begin to see themselves, others, and God in new ways, knowing the importance of the “new couch” even when the student cannot see it yet? This is the good work of being with students as they take risks and discover their calling. However, if we move the furniture too much, they may not recognize their place in the room anymore. In the end, for the sake of the leveret and her commitment to having it in her life, Dalton chose to put the old couch back in the living room. In our line of work, we are at times responsible for moving a new couch in and helping students live with the discomfort until they come to see the “new couch” for what it is. Yet, in other equally sacred seasons of a college student’s life, we are responsible for hauling the old couch back into the living room, so they can feel the comfort and safety of “their spot”—to remember who they are, and who God has created them to be—before embarking on a collegiate journey that we hope will ultimately be life changing.

In the end, I came to see that the leveret Dalton brings into her home and the college students I have known have a lot in common. Both the student and the leveret, by development and design, are curious and endlessly inquisitive creatures. They both require long hours of sleep, having the ability to lounge in any place and under almost any circumstances when they are inclined to do so. The leveret and college students can be perpetually hungry and can be at times quite picky eaters with a need for regular activity to keep both their minds and their bodies healthy. They are also social creatures. Leverets learn, in the same way that college students eventually do, the importance of a band, a husk, a warren, a drove, a flick, or a down—a community—of other hares in which to live, play, and learn. If I imagine it long enough, I can see the students at my own college bounding across the center of campus, ears alert to their surroundings as they dart in all directions with their noses pointed to the sky, sniffing at the scent of the world beyond their home range and visibly wondering what lies beyond. And I am grateful that both also have a strong desire for routine and familiarity.

It will then be no surprise that college students, just like leverets, mature quickly, develop habits and unique interactions, display interests, keep secrets, build trust, seek adventure, and are at their very core, wild. The trial and error it took Dalton to understand that the leveret should not be caged but allowed to run free felt true of my work with college students as they are learning to be who God has called them to be. Raising Hare offers a reminder of the joys and the challenges of working with young people as they discover their futures; the book also offers a reminder of the importance of letting go and encouraging our students over the garden walls of the familiar and into the new wild spaces they seek.

To report a technical problem with the website, or to offer suggestions for navigation and content issues, please contact Alex Stephenson, NetVUE communications coordinator, at astephenson@cic.edu.